Getting Rid of Attention Seeking Machines: How to. by Dahsa Ilina

The first cell phone I owned was a silver Motorola with light blue sides. It had a color screen, a camera, buttons you could actually press, but more importantly it seemed to contain the whole world. While trying to find a picture of this phone on the internet, I came across the product page for it on the website belonging to an electronics shop. The top review dated from 2013 and read: “my sister said that if she doesn’t have this phone, she will jump from the 15th floor.” While obviously intended as a joke, this comment shows I wasn’t the only one completely obsessed with what would now be considered a dumb-phone. From that day forward, my obsession with telephones only grew. Though with the best of intentions, I still spend on average about three hours a day on my phone, which makes me question what it is about portable technology that always leaves me, or rather us, wanting more?

Of course there is no one answer to that question. Countless studies have been made that point to the color of the notifications, or the sound of the alerts, being the reasons behind our modern obsession, and while those may amplify the effects, I don’t think that bright red notifications are the only reason I can’t stop looking at my screen. At this point, I would like to make it very clear that I do not have a perfectly justifiable reason, but seeing as my first Motorola stole almost as much of my attention as my iPhone does, I would like to argue that at least my addiction to technology stems from far before the dawn of smart devices.

Let’s consider another gadget — a computer. I find that addiction to laptops or desktop computers is significantly less of a trending topic than our phone usage. However, computers were definitely the technological folk devils of their time, in precisely the same manner as smartphones are today. To bring in another personal example, I remember clearly how, in middle school, I began waking up at three in the morning every night for several consecutive weeks to play video games on our family computer, conveniently located in my bedroom. My grades in school subsequently plummeted because I, rather predictably, became my school’s biggest somnambulist. Simultaneously, my popularity level only increased, since I was able to talk to my other zombie-classmates in the game chat at night, and in my semi-sedated state tell the others about my progress the following day. So could it be that the social aspect behind technology is what makes it so potent? Does the ability to connect with whomever you want whenever you want, attract the user to the point of no return? I would argue that this was the case ten years ago, notably before the introduction of apps. I say this mainly because most of the time I spend on my phone now, I end up disconnecting from the people around me, in the chase for the elusive online connection. Though there must be solutions to this problem, right?

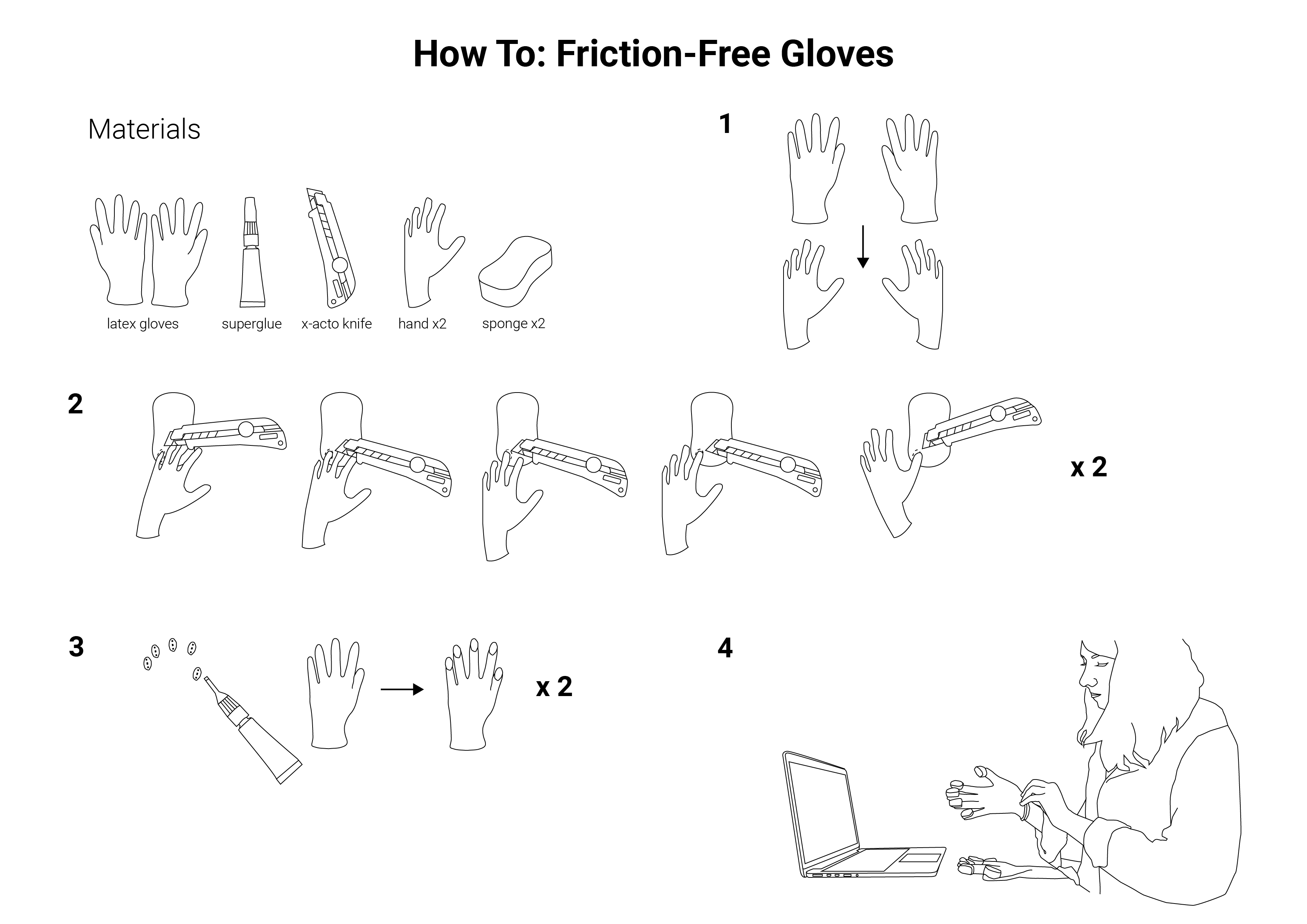

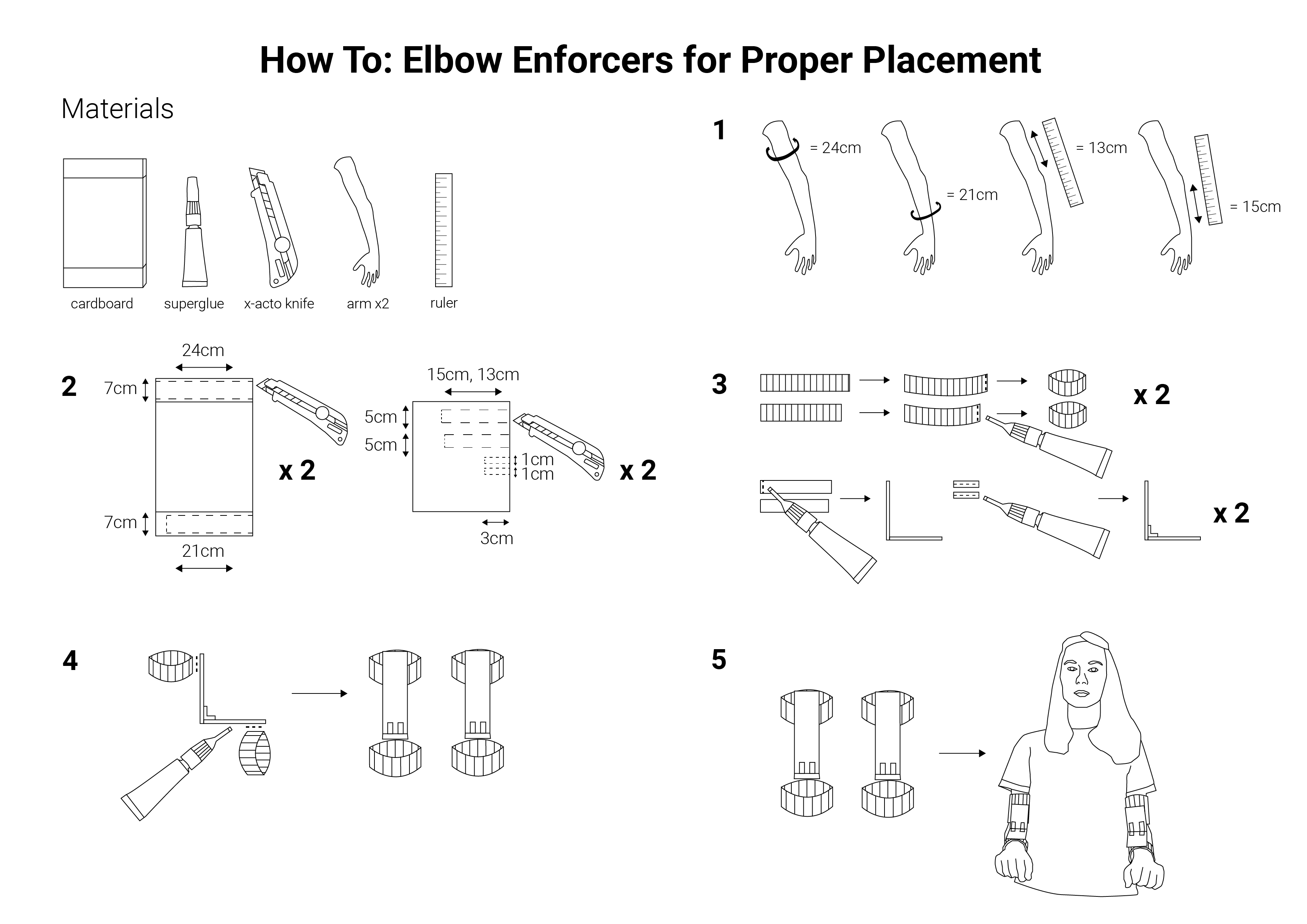

While tech companies try implementing programs to temporarily disable apps for your “productivity”, and even Google proposes a program for digital wellness (https://wellbeing.google/), it becomes clear (and possibly should’ve been clear all along, given the contradictory nature of the solution proposed) that no additional software can solve the problem of tech-addiction. But addiction to technology does not only manifest itself in its detrimental effects to our social lives; think of all the physical pain one experiences on a daily basis, from neck pain to eye dryness, certain health problems have become synonymous with technology and the workplace. Even though designers have recently started proposing fancy objects to get rid of such problems, just as additional software won’t solve tech-addiction, design objects likely won’t put more than an Apple Watch sized dent in the issue of tech-pain either. That being said, I have spent over two years researching the subject and producing, among other things, objects for preventing tech-pain. So what’s the catch? How are my objects and those I just bad-mouthed one minute ago different in any significant manner? The crucial difference is I don’t sell my objects, nor do I promise that they will get rid of all of your problems (or any of them, really). My DIY solutions to tech-pain take the shape of ridiculous looking devices made, more often than not, out of cardboard. They get the job done, but they don’t last more than a few days. Lucky for me the point behind creating these objects is not to make something durable. These objects, and more specifically the process behind making them, are intended to stimulate discussion around our intrusive devices and all the reasons why we can’t let go of them. But the best part about the process is that it’s fun to make things with your hands, especially for adults who have long ago forgotten what it’s like to spend 3 hours cutting and glueing things.

So with that in mind, I present to you a few tutorials that show how you can create solutions to tech-pain in your own home.

This was a contribution published in Coded Bodies Publication in 2020